Welcome toCafe SongbookInternet Home of the |

|

|

| Home || Songs || Songwriters || Performers || Articles and Blogs || Glossary || About Cafe Songbook || Contact/Submit Comment | |

| Search Tips: 1) Click "Find on This Page" button to activate page search box. 2) When searching for a name (e.g. a songwriter), enter last name only. 3) When searching for a song title on the catalog page, omit an initial "The" or "A". 4) more search tips. | |

You'll Never Know |

|||

Written: 1943 |

Music by: Harry Warren |

Words by: Mack Gordon |

Written for: Hello, Frisco, Hello (movie, 1943) |

| Page Menu | |||

| Main Stage || Record/Video Cabinet || Reading Room || Posted Comments || Credits | |||

On the Main Stage at Cafe Songbook | |||

(Please complete or pause one video before starting another.) |

Rosemary Clooneyperforming "You'll Never Know"with Les Brown and His Band of Renown Find Rosemary Clooney recordings of

More Performances of "You'll Never Know" |

||

Cafe Songbook Reading Room"You'll Never Know" |

||||

| About the movie, Hello, Frisco, Hello, and the Origins of the Song | ||||

|

The movie Hello, Frisco, Hello springs from the same plot template as the show Pal Joey that opened three years earlier on Broadway. Both stories involve a young cheap-district entertainer (and eventually club owner) who aspires to climb the ladder to success on the other side of the-tracks. Both men manage this, at least for a while, by hooking up with wealthy heiresses at the expense of the women who really love them. There are, of course, many differences as well, but it is interesting to note that the 1957 movie version of Pal Joey is set in the same two San Francisco neighborhoods as Hello, Frisco, Hello is: The low-brow Barbary Coast and the affluent Knob Hill. In Hello, Frisco, Hello, the innocent woman whose heart gets broken by the ambitious young man who marries someone else for money, is the girl singer, Trudy Evans (Alice Faye). She is a singer in a struggling group of entertainers that includes the man she loves, Johnny Cornell (John Payne). The movie opens with Trudy on stage playing a young woman talking to her love long distance on the newly invented telephone. Supposedly away on business, he is only on the other side of the set, a visual metaphor in the on-stage sketch for the distance that is delaying what will soon be their romantic reunion. It is also, however, a foreshadow of the distance between between Trudy and Johnny that will develop as their off-stage story unfolds. The movie's first musical number is the over-the-telephone "Hello, Frisco, Hello," which transitions into Trudy's character singing -- presumably after Johnny's character is off the line -- "You'll Never Know (just how much I miss you)." Although the song is part of the sketch, it is also a reflection of her real, apparently unrequited, feelings for him. Hello, Frisco, Hello (like Pal Joey) is a "backstager," a story about singers, dancers, musicians etc. who are involved with each other on stage as characters is a show and backstage as real people. [To listen to the soundtrack from the film that includes "Hello, Frisco, Hello" and "You'll Never Know, go to the Cafe Songbook Record/ Video Cabinet, this page] During the remainder of the film, Johnny works his way up, first as the owner of several honky-tonks, then some higher class clubs, and finally, in connection to his love affair with and marriage to heiress Bernice Croft (Lynn Bari), to becoming owner of the San Francisco opera house. Trudy, of course, is devastated by the marriage, but continues her career by accepting an offer to perform in London where she becomes very successful and rich on her own. When Trudy returns to San Francisco it is just in time to save Johnny, who, having divorced Bernice, is on the brink of financial disaster. She uses both her money and talent to help him with his new show-biz venture back in the old neighborhood -- where they both belong. Trudy sings "You'll Never Know" twice more. Closure is achieved when it is sung during the finale, performed as a duet, recalling the duet that opened the movie, now foreshadowing the couple's future together: successful on-stage and in love off-stage. Harry Warren and Mack Gordon wrote only one song for Hello, Frisco, Hello, but it was good enough to outshine the multiple turn-of-the-century period numbers, as delightful as they are, that are performed throughout the film. It was also good enough to win the Academy Award for best original song for 1943. One factor that separated "You'll Never Know" from the film's other songs was that even though it was sung by performers on a stage -- an artificial setting -- its lyric was integratedinto the off-stage part of the story.

The film barely references World War II, which was raging while the movie was being made, as well as after its release. (One of the intentions of the film makers was undoubtedly to take the audience's minds off the war -- a common objective in movies made during the early forties.) In any case, such a reference would have been difficult because of the movie's 1890's setting. Nevertheless, The last production number features a chorus of sailors and sailorettes on a battleship, a clear a reminder to contemporary audiences of the the reality from which this film was helping them to escape. Warren and Gordon were mindful of the war also. Tony Thomas writes, "You'll Never Know" was no ordinary song. It was instantly popular and within a few months became almost an anthem of the Second World War." Thomas quotes Warren talking about his best selling song (for sheet music) of all time:

Philip Furia and Michael Lasser find it curious that Warren got his inspiration for the song from a military source. They quote Warren saying to a friend:

Tony Thomas's contention that "You'll Never Know" turned out to be "almost an anthem of the Second World War," is supported by the use of the song in the 1944 movie Four Jills and a Jeep, (starring Kay Francis, Carole Landis, Martha Raye, and Mitzi Mayfair as themselves, re-enacting their USO tour of Europe and North Africa earlier in the war). It is again sung by Alice Faye, in a cameo appearance playing herself, sending the song to the boys overseas.

|

|||

Alice Faye Collection 2 (Rose of Washington Square/Hollywood Cavalcade/The Great American Broadcast/Hello, Frisco, Hello/Four Jills in a Jeep)

|

||||

|

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

| Critics Corner | ||||

|

Gary Marmorstein compares two of Harry Warren's writing partners, Al Dubin who wrote with Warren at Warner's until personal problems forced the lyricist out of the picture, and Mack Gordon who was paired with Warren upon the composer's arrival at Twentieth Century Fox in 1940:

|

|||

Wilfred Sheed, The House That George Built: With a Little Help from Irving, Cole, and a Crew of About Fifty |

Wilfred Sheed, a great admirer of Harry Warren's music, is ambivalent about Gordon's words, especially their poetic qualities. Gordon, Sheed writes, "offers an advanced lesson in why good song lyrics don't have to be great poetry. For a reputed Windbag, he had a wonderful ear for the regular phrases people were using that year. . . . and an even better ear for fitting them to the right notes." Still, "it wasn't literary and singers with a taste for good writing tend[ed] to shy away from Gordon's lyrics. Even songs as successful as ballads like "You'll Never Know," "At Last" and "The More I See You" have, for Sheed, employ words that are "consistently undistinguished" and "second class," and are only "saved by the music" (Sheed, p. 217). | |||

Philip Furia, The Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America's Great Lyricists, New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. |

Philip Furia is also ambivalent about Gordon's words. He cites "You'll Never Know"as "an open invitation to sentimentality" which is then counteracted by "hard-edged vernacular phrases" producing a comic effect:

|

|||

Philip Furia and Michael Lasser, America's Songs: The Stories Behind the Songs of Broadway, Hollywood, and Tin Pan Alley, |

By the time Furia joins Michael Lasser in their book America's Songs, Gordon receives a warmer reception. They still point out the weakness deriving from the lack concrete imagery; nevertheless, Furia and Lasser find "You'll Never Know" if still sentimental "convincing despite the abstraction of the lyric. If it's weakness is a lack of imagery and the absence of a narrative it becomes "persuasive through a combination of hushed romanticism in the melody and whispered passion in the words:

This led at the time of its original popularity to "a sustained tone of private longing" that created a poignant response during the war, especially in women.

Presumably lovers don't have to be separated by war to continue to respond to the feelings expressed in "You'll Never Know." |

|||

| back to top of page | ||||

| Lyrics Lounge | ||||

|

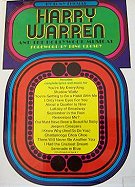

Click here to read the lyrics for "You'll Never Know" as sung by Frank Sinatra on various albums including The Columbia Years 1943-1951, Vol 1. Sinatra does not sing the verse, but it is included at the above link, where it is called the "intro." You can also listen to the verse on the following recordings on this page: The lyrics (with the music) as originally published can be found in Tony Thomas (with forward by Bing Crosby) Harry Warren and the Hollywood Musical, Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1975

Click here to read Cafe Songbook lyrics policy. |

|||

| back to top of page | ||||

Visitor CommentsSubmit comments on songs, songwriters, performers, etc.

Feel free to suggest an addition or correction. Please read our Comments Guidelines before making a submission. (Posting of comments is subject to the guidelines. Not all comments will be posted.) |

| To submit a comment, click here. |

Posted Comments on "You'll Never Know":

No Comments as yet posted |

| back to top of page |

Credits("You'll Never Know" page) |

Credits for Videomakers of videos used on this page:

Borrowed material (text): The sources of all quoted and paraphrased text are cited. Such content is used under the rules of fair use to further the educational objectives of CafeSongbook.com. CafeSongbook.com makes no claims to rights of any kind in this content or the sources from which it comes.

Borrowed material (images): Images of CD, DVD, book and similar product covers are used courtesy of either Amazon.com

Any other images that appear on CafeSongbook.com pages are either in the public domain or appear through the specific permission of their owners. Such permission will be acknowledged in this space on the page where the image is used.

For further information on Cafe Songbook policies with regard to the above matters, see our "About Cafe Songbook" page (link at top and bottom of every page). |

The Cafe Songbook

|

||||

|

Performer/Recording Index

(*indicates accompanying music-video)

|

||||

1943 and 1944

Notes: Alice Faye performed "You'll Never Know" in two films (Hello Frisco, Hello," 1943 and Four Jills in a Jeep, 1944) but never made a separate recording of the song that was at first identified almost exclusively with her.

(Please complete or pause one video before starting another.) |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

1943 and 1955

Notes: The "You'll Never Know" track on the album above is Haymes 1943 chart hit. For a detailed and informative description of the content of the album as a whole, use the Amazon customer review by AvidOldiesCollector 1955

Notes: "In 1955, Capitol Records signed Dick Haymes and attempted to do for him what it had done for Frank Sinatra a few years earlier, resurrect his career. Due to a combination of personal and business problems, Haymes had fallen far from his mid-'40s peak, when he was a major rival to Sinatra among the new crop of solo singers emerging from the big bands. The Capitol sojourn led to 12 recording sessions between December 20, 1955, and April 4, 1957, that produced two LPs, Rain or Shine and Moondreams, and a few singles, only one of which, "Two Different Worlds," managed a brief stay in the charts. The recordings were out of print for decades, but were championed by some critics, making this thorough two-CD set, compiled by Ken Barnes, a welcome reissue" (from iTunes review). the "You'll Never Know" track is a studio recording from 1955 made for the album Rain or Shine. |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

1943

Notes: The full box set of The Columbia Years contains 254 tracks. Many of these are available on smaller less expensive CD's. For a selection of these at Amazon, click here The Sinatra recording on the Columbia Years album above is the same as that which became a #1 hit in 1943, his first recording for Columbia as a solo artist. He was accompanied by The Bobby Tucker Singers and no instrumentalists because the recording session took place while The American Federation of Musicians was on strike, a strike that continued from 1942-1944 and changed the recording industry. There is a second recorded version of "You'll Never Know" by Sinatra, from a 1943 live radio broadcast, his weekly program Songs by Sinatra, on which Frank is accompanied by Axel Stordahl and orchestra as well as the Bobby Tucker Singers, live recordings apparently not affected by the above mentioned strike. The recording and more information about it can be found on the Sinatra box set, A Voice in Time 1939-1952 (W/Book).

|

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

1952

Notes: Clooney's first album for Columbia Records, Hollywood's Best, featured her vocals with Harry James and his orchestra and includes the recording of "You'll Never Know," one of her first, that she refers to in her live performance on the Cafe Songbook Main Stage above and that can be heard on the music-video above. In its first incarnation the album was an eight-song, 10" LP in 1952. Then it was expanded to a 12 track, 12" LP, which has been re-released on the CD above. It is also available as half of a "twofer" (two LPs on one CD -- Hollywood's Best and Ring Around Rosie (1957) -- just below.

(Please complete or pause one |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

1954

Notes: "This collection features Big Maybelle's entire Okeh output — 26 tracks — including her three R&B chart items, "Whole Lotta Shakin' Goin' On," and the risqué slow blues "I'm Gettin' 'Long Alright." "Gabbin' Blues,". . . . New York session wizards such as tenor saxophonist Sam "The Man" Taylor and guitarist Mickey Baker provide great support throughout" (from iTunes review). Big Maybelle's version of "You'll Never Know" takes some liberties with the melody while making the song her own. |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

1955

Notes: "If you have all the Songbook albums that Ella Fitzgerald recorded, and want to swell your collection further, this CD will undoubtedly appeal, as it covers the period in the run-up to her trendsetting 1956 Cole Porter record. Four of these 1955 tracks [including "You'll Never Know"] were conducted by Andre Previn, and are sumptuous, classy, strings-accompanied interpretations of classic ballads. Another six numbers - the "Hot" of the title - are fast, seriously swinging standards with jazz maestro Benny Carter at the helm. My favorite tracks : 'You'll Never Know,' [and] 'Between The Devil And The Deep Blue Sea.'" (from Amazon customer reviewer smooth jazz views If you're so interested in Ella's Decca period that you will need even more than the above album to satisfy you, look at the 80 track set Ella: The Legendary Decca Recordings, which includes all of the tracks from Sweet and Hot--plus 69 others. See the iTunes review

(Please complete or pause one |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

1955 and 2000 CD: Just for the Record (1955)

Notes: One of Barbra Streisand's earliest recordings, if not her first, was "You'll Never Know" recorded on December 29, 1955 at Nola Recording Studios in New York City when Barbra was 13. This is the first track on Just for the Record and can be heard on the video above. Some forty-five years later in her Timeless Concert, which includes moments from Streisand's New Year's Eve, 1999 and New Year's Day, 2000 shows in Las Vegas, she opened with "You'll Never Know," and reprised it later in the show in combination with "Papa, Can You Hear Me?" (Michel Legrand, music and Alan and Marilyn Bergman, lyrics, from the film Yentl, 1983). In this performance, she is joined by Lauren Frost, who according to Streisand is playing her as a girl, likely the girl who made her first record ("You'll Never Know") when she was thirteen and so missed her father who had died when she was only fifteen months old.

It should also be noted that in the long intro that preceded her entrance in the Back to Brooklyn concert in 2012, the main theme was "You'll Never Know." Watch at YouTube. |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

1959

Notes: This is the complete, original 1959 album Oscar Peterson Plays the Harry Warren & Vincent Youmans Songbooks (Verve MG V6-2059), appearing for the first time ever on CD (2011). |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

1969

Notes: This CD is a twofer including two Stitt LPs from the sixties: The 1963 Soul Shack (with organist Jack McDuff, bassist Leonard Gaskin and drummer Herbie Lovelle) constitutes the first six tracks and the 1969 Night Letter (with organist Gene Ludwig, guitarist Pat Martino, and drummer Randy Gelispie) takes care of the balance. "You'll Never Know" was originally released on Night Letter. Amazon customer reviewer J. Levinson writes, "The up-tempo "You'll Never Know" is one of the highlights, with drum breaks from Gelispie punctuating the sax, organ, and guitar solos." |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

1983

Notes: In 1978, Willie Nelson began his new persona as a troubadour of The American Songbook with his album Stardust, a collection of standards that was so successful that it led to a series of other Songbook albums. Without a Song is the third in the series. The second was Over the Rainbow and the fourth, What a Wonderful World. For Without a Song, Nelson brought back Booker T. Jones, the producer and arranger on Stardust and the album has the feel of their earlier collaboration. |

||||

1998

Notes: "The title of this recording is doubly significant. While the late guitarist's interpretation of Irving Gordon's immortal composition is certainly representative of this collection of standards, it's Joe Pass himself who must be considered unforgettable. A master of technique, Pass first gained prominence as an industrious studio musician in the early '60s. After years as a sideman with George Shearing, Benny Goodman, and Ella Fitzgerald, among others, Pass worked as a solo artist until his death in 1994. This batch of classics performed on the acoustic guitar was recorded in 1992 and displays the man's accomplished fingerpicking technique and strength as a soloist. From emotive interpretations of 'Autumn Leaves' and 'Moonlight in Vermont' to his bopping version of Monk's ''Round Midnight,' this is timeless Pass." --Mitch Myers Amazon Editorial Review |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

2000

Notes: The album features John Pizzarelli on vocals and guitar, Jessica Molaskey (john's wife) on vocals, Ray Kennedy on piano, Tony Tedesco on drums, Harry Allen on saxophone, Dominic Cortese on accordion, Jesse Levy on cello, Ken Peplowski on clarinet, Martin Pizzarelli on bass, and the incomparable Bucky Pizzarelli (John's and Martin's father) on guitar (seven string). |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

2001

Notes: "Kristin Chenoweth capped a rising career in musical theater with her debut solo album, which found her showing off her well-trained soprano in a collection of show tunes, most of which dated to the interwar period. On Irving Berlin's 'Let Yourself Go,' she tap danced like Fred Astaire in Follow the Fleet, and she worked up a torrent of comic anger in Jule Styne's 'If You Hadn't But You Did.' Then, she switched gears, proving herself a potently romantic figure in the Gershwins' 'How Long Has This Been Going On?' and Rodgers and Hart's 'My Funny Valentine.' And so it went. Backed by the Coffee Club Orchestra, the resident backup band for City Center's Encores! series of concert versions of lost musicals, with whom she had worked on Strike Up the Band and On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, she recreated one of the Strike Up the Band numbers, the lesser-known Gershwin treat 'Hangin' Around With You,' abetted by another musical theater veteran who had branched out into TV, Jason Alexander. Jeanine Tesori and Dick Scanlan's previously unheard 'The Girl in 14G' allowed her to show off her opera training as well as her scatting abilities, and she fearlessly (and successfully) took on the ghost of Mary Martin by covering 'I'm a Stranger Here Myself' from One Touch of Venus. Like an elaborate audition tape, the album seemed designed to suggest that Chenoweth could play any sort of part; sometimes the songs themselves reflected this goal of displaying versatility, notably the obscure Vincent Youmans song 'Should I Be Sweet?,' in which the singer must bounce back and forth between 'sweet' and 'hot' personas as she tries to choose between them. But whatever role she undertook, Chenoweth revealed more than enough talent to excel on a dazzling first album." (iTunes album review) |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

2004

Notes: "A performer following in the illustrious steps of Frank Sinatra, Michael Bublé offers a contemporary revamp of old swing sounds on this live release. By taking a daring sideways step that most in the fashion conscious music industry wouldn't dare, Bublé has won over a solid fanbase for his old-time tunes. These performances were captured in London, New York, Hollywood, and South Africa." from CDUniverse.com. album personnel: Alan Chang, piano; Brian Green, guitar; Robert Marshall, saxophone; Evan Francis and Jason Goldman, alto saxophones; Justin Ray, Brian Swartz and Bryan Lipps, trumpets; Karime Harris and Nick Vagenas, trombones. For good overview, see iTunes review. |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

2007

Notes: Indian Summer "is something of a companion piece to 2004's Private Brubeck Remembers. Like that gem, Indian Summer is a solo piano work comprised of Brubeck's ruminations on standards of the mid-20th century, the period when he was just coming up as an artist and blossoming as a young man. These are reflective, meditative ballads, softly but skillfully played and hinting at melancholy. . . . Brubeck is restrained but soulful, out to prove nothing. It's not that age has dulled him. . . . Brubeck's performance is uniformly exquisite, imaginative, and elegant; it's just not edgy" (iTunes Review). |

||||

| back to top of page | ||||

2012

Notes: On her You'll Never Know Track," Raney and Broadbent do the verse. The following review of their album Listen Here by Christopher Loudon is from JazzTimes.com. One of the most underappreciated jazz vocalists of the past half-century, Sue Raney is also proving one of the most durable. Raney, who has been singing professionally since age 14, delivered a trio of excellent albums for Capitol while still in her teens and early 20s, then endured a peripatetic recording career that involved multiple labels and occasionally lengthy gaps (filled with teaching and jingle work—as both writer and performer). Through it all, she has never stopped plugging and, remarkably, still sounds as vibrant and clarion-pure as ever.

In recent years, Raney has formed a mutually beneficial alliance with pianist Alan Broadbent. It was Broadbent at the helm, as arranger, conductor and accompanist, on Raney’s previous album, the silken Doris Day tribute Heart’s Desire. Here it’s just Broadbent and Raney, two thoroughbreds shaping an exemplary exercise in simpatico intimacy. They open with Dave Frishberg’s tenderly introspective “Listen Here,” then keep the tempo on simmer through a spectrum of major league ballads, extending from the romantic coziness of “My Melancholy Baby” and “You’ll Never Know” to the hazy heartache of “He Was Too Good to Me” and “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” The pace quickens slightly for a sprightly “It Might as Well Be Spring” and a shimmering “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square.” But the standout piece in this sea of marvelous tracks is Raney and Broadbent’s gorgeously realized treatment, neither too maudlin nor too wistful, of Joe Raposo’s “There Used to Be a Ballpark.”

|

||||

| back to top of page |

| Home || Songs || Songwriters || Performers || Articles and Blogs || Glossary || About Cafe Songbook || Contact/Submit Comment | |

© 2009-2018 by CafeSongbook.com -- All Rights Reserved |